Epistemic Arrogance

A cause of difficulty in discerning truth, loss of trust in institutions, and catastrophic disasters.

Introduction

How many times have you heard or read a sentence starting with a phrase such as “We know X” or “The facts show X”, only for it to later be revealed that what we allegedly knew about X was false? How many times have you come across a bold and confident assertion, which either time or further detail revealed to be wrong? Here’s a fitting example, given the name chosen for this blog, taken from the Inquisition’s sentencing of Galileo Galilei in 1633 for heresy.

“And whereas this Holy Tribunal wanted remedy the disorder and the harm which derived from it and which was growing to the detriment of the Holy Faith, by order of His Holiness and the Most Eminent and Most Reverend Lord Cardinals of this Supreme and Univesal Inquisition, the Assessor Theologians assessed the two propositions of the sun's stability and the earth's motions as follows: That the sun is the center of the world and motionless is a proposition which is philosophically absurd and false, and formally heretical, for being explicitly contrary to Holy Scripture; That the earth is neither the center of the world nor motionless but moves even with diurnal motion is philosophically equally absurd and false, and theologically at least erroneous in the Faith.”

A few hundred years later, and now we’re all quite comfortable (including the Catholic church) admitting that the Earth is neither the center of the universe nor motionless.

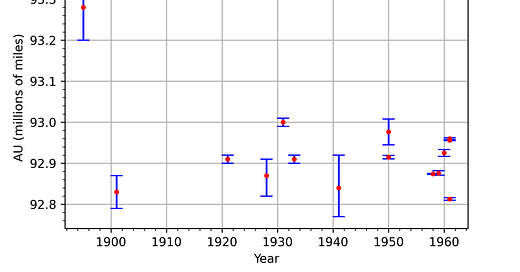

This idea can apply to numerical data as well, albeit more subtly. As an example, let’s look at the calculation of the mean distance from the Earth to the Sun, called an Astronomical Unit (AU). In a paper written in 1972, Youden compiled several measurements that had been taken of this value over the previous 80 years. In addition to the measurements, Youden included the error bars for the measurements, a tool used to give an indication of how much error or uncertainty is expected to be in the measurement. This error or uncertainty could come from any source. One potential source is instrument precision. If you’re measuring the length of something and all you have is a ruler, you probably can’t get much more precise than plus or minus half a millimeter or so. If you’re trying to measure how much something weighs and all you have is my crummy bathroom scale which operates in increments of 0.2 lbs, then your instrument can’t tell the difference between 180.1, 180.15, or 180.29 lbs. They all just register as 180.2 lbs. A plot of such a measurement would stick a data point at 180.2, the measured value, and then extend error bars around the data point from 180.1 to 180.3 to indicate that the true value could actually lie anywhere within that range. I’ve plotted the data (in red) and error bars (in blue) from Youden below.

The earliest measurement, taken in 1895, is somewhat of an outlier, but the other remaining measurements are all clustering around 92.9 million miles. Seems good, right? Take a closer look at those error bars. How many of the error bars overlap with one another? Put another way, how many of these scientists agree on what a possible range for the value of 1 AU is? If my crummy bathroom scale tells me I’m somewhere between 180.1 and 180.3 lbs, but your crummy bathroom scale tells me I’m somewhere between 182.5 and 182.7 lbs, which is it? They can’t both be correct. These scientists were explicitly trying to account for the uncertainty in their own methods, and they still obtained results with this little overlap. Presumably the true value is somewhere in this region, so some and likely most of the scientists are wrong, at least in their assessment of their own uncertainty. Even more gallingly, Rabe in 1950 and S.T.L. in 1960 report their data out to six significant digits. Six! The rest of the field is still arguing over what the third digit is, but these researchers are somehow confident enough to assert they know what’s going on with 1000x that level of precision? There’s clearly some erroneous thinking here.

Let’s look at another trend in the data. The error bars are roughly decreasing in range over time, particularly so after 1941. This indicates that the researchers have a higher degree of confidence in their results, probably due to improvements in equipment and finely tuning their methods to reduce statistical noise. If warranted, then this reduction in error bars is great. It should mean that we’re getting closer to the true value. Now look at the scatter in the data points. Putting aside the outlier point from 1895, the values from 1901 to 1941 across all researchers range from a little over 92.8 million miles to 93.0 million miles. And the values in later years, after the error bars have been reduced, range from... a little bit over 92.8 million miles to a little bit under 92.96 million miles. There’s a slight tightening of the min and max bounds across investigators, but it’s not big. There is even less overlap in the error bars in the later years though. So most of the researchers in these later years are still wrong, at least in their assessment of their own uncertainty. Thus, we come to the worrying conclusion that the researchers are still (nearly) as wrong as they were in earlier years, but they have become more confident in their wrong answers.

What’s going on here? The important thing to recognize is that errors and uncertainties can exist in multiple forms. One form is random uncertainty, caused by measurement noise or inherent variability in a system. To deal with this form of uncertainty, we have the full power of probability and statistics to aid us. A more insidious form of uncertainty is systematic, or epistemic, uncertainty. This is more difficult to deal with. Systematic error is what results when there is consistent error across all of your measurements. Perhaps your instrument is off, or your calibration is wrong, or something about your theory of how the system works is incomplete, and it’s leading to all of your measurements being wrong in the same way. Youden points out that “each investigator’s reported value is outside the limits reported by his immediate predecessor. I draw the conclusion that these investigators simply do not have reliable information about their systematic errors.” Basically, there was some unknown error that was biasing the results up or down. If the presence of errors is known, as in random variations or limited instrument precision, then steps can be taken to mitigate them. We can see this in the reduction of error bars in the above plot. In the case of unknown systematic errors though, or Donald Rumsfeld’s infamous “unknown unknowns”, you’re screwed. You end up with the situation shown in 1961 in the above plot, where there are four distinct groups that all have extremely high confidence in their own view while disagreeing with everyone else’s equally self-confident view.

Here’s one more recent and hair-raising example of misplaced confidence in an assertion that proved to be wrong.

The above quote, and the thinking behind it, led directly to the deaths of an estimated two hundred thousand people in the Iraq war. There were not weapons of mass destruction.

There’s a common thread that links the above examples together. What they have in common is what I think of as epistemic arrogance. The definition of epistemic is “relating to or involving knowledge”. Therefore, epistemic arrogance is being arrogant about the state of your own knowledge. The opposite would be epistemic humility, which is being humble about the state of your own knowledge. Someone who displays epistemic arrogance is absolutely convinced that they are right, they understand the situation perfectly, they know exactly what is going to happen. Their knowledge is perfect, there is no uncertainty, and nothing is unaccounted for. Someone who displays epistemic humility acknowledges that they may not understand everything, there can be missing variables, or their model may be imperfect. There is uncertainty, and it is acknowledged. (Granted, in the AU example, the researchers did acknowledge their uncertainty, even if they were off in their assessment of it. The epistemic arrogance in this case has more to do with reporting ludicrously high precision in the presence of such uncertainty.)

The Importance of Epistemic Humility

Being more confident or bolder is good advice for dating, but terrible advice for pursuing truth. People are drawn to confidence. It makes for fun friendships, inspiring leaders, and passionate relationships. In contrast, a lack of confidence can be interpreted as meekness or even weakness. In a social context, it’s repulsive. The situation is reversed in truth-seeking. Uncertainty must be acknowledged when the truth is being sought, and being overly confident is reckless. Epistemic humility is a virtue that helps us arrive at truth, whereas epistemic arrogance is a vice that impedes and endangers us.

Suppose you live in a coastal state, and there’s a hurricane approaching. It’s still a few days away, but you check the weather and they report that models show the storm will make a sharp turn to the East and completely miss you. You breathe a sigh of relief and start to think about other things. Two days later you wake up and your house is underwater. What went wrong? A process with natural uncertainty in the model was reported on as if everything was certain. The people that aren’t familiar with the inner workings of the model and exist downstream of it take it at face value, unaware that reality may turn out very differently. This leads to disastrous outcomes. If the uncertainty had been reported, say as a 25% probability that the storm wouldn’t turn to the East, then you could adjust your preparations and your attention accordingly. Given that probability, you don’t need to panic, but you definitely can’t afford to ignore things either. In this secondary hypothetical scenario, in which you do continue to pay attention due to the remaining uncertainty, you notice as the best estimate changes and it becomes apparent that you need to make emergency plans or evacuate. Disaster is mitigated.

In the real world, as opposed to the hypothetical world of the previous paragraph, hurricane forecasting is actually pretty good about acknowledging uncertainty. Whenever there’s a storm, the weather channel will put up graphics that display a cone with the most likely trajectories. This is a natural way to communicate that there’s some uncertainty about where the storm is going to go, and that as projections are made further into the future, the uncertainty grows. Sometimes you can even see the results of different uncertain models plotted against one another. These are all helpful and honest ways to communicate valuable information. Once that information is communicated, the people that it’s relevant to can make whatever plans they need to based on the expected outcome, an optimistic outcome, or a cautious outcome. This level of honesty and transparency is the sort of epistemic humility we should be striving towards.

Note that what I’m advocating for here is distinct from pulling a Socrates. By this, I’m referring to the quote attributed to Socrates where he is claimed to have said something along the lines of

“if I am the wisest man alive, it is for I know one thing, and that is that I know nothing” – Socrates, probably.

This is a cop-out done by cowards in the face of uncertainty. Just because there is uncertainty doesn’t mean we get to claim we don’t know anything. We still possess the tools to measure values, the concepts to explain phenomena, and the principles to explain trends. We still have math. Once we acknowledge that uncertainty exists, the next step is to minimize it so that we can get closer to the truth. Minimizing uncertainty may consist of upgrading measurement devices, running more experiments, collecting more samples, gathering more information, exploring different variables, searching for hidden biases, or all of the above. Striving for epistemic humility means acknowledging the existence of uncertainty and then doing your best to figure things out in spite of it, not giving up and throwing in the towel because things are hard and you don’t want to try.

Consequences of Epistemic Arrogance

What happens when individuals, or even worse, institutions start to display epistemic arrogance? The first thing that happens is that truth becomes more difficult to converge upon. Unacknowledged errors, random, systematic, or both, accumulate unmitigated. You calculate that some important value is equal to A, but in reality it’s equal to B. Someone else builds off of your work, using your ideas and results to inform their own work, unaware of the mental shortcuts you took in yours. The house of cards grows.

Next, technology and hypotheses downstream of your ideas start to fail because your calculation was wrong. The car cabin structure predicted to keep its passengers safe in a 60 mph crash crumbles in a 45 mph crash. The naval vessel designed for a service lifetime of 20 years is decommissioned in half that time because the aluminum hull and steel engine corrode in salt water. Years worth of published scientific papers in an entire discipline need to be thrown out because they were built on a faulty foundation.

At higher levels, repeatedly getting things wrong leads to a loss of trust. In the case of institutional epistemic arrogance, catastrophic errors can occur because you thought you knew something that was totally bogus. Once trust is lost, either in an individual or an institution, it may not be repaired for a long time, if ever. This is the case of the Iraq war.

At the highest and most severe level of epistemic arrogance, there is not only arrogance about a state of knowledge, but a mechanism of enforcement upon others who would challenge the arrogant claims. This is the case of the inquisition, as described earlier that hounded Galileo. For the crime of pursuing truth and rejecting the claims of the epistemically arrogant, he was sentenced to house arrest for the rest of his life.

Countering Epistemic Arrogance

The most important thing that can be done to ward against epistemic arrogance in an individual is to embrace the idea of epistemic humility. Think in terms of probabilities rather than absolutes, as in the hurricane example. It’s ok to acknowledge uncertainty. Even if your assessment is off, as in the AU example, opening yourself up to the possibility that there’s room for improvement is valuable. It’s ok to not have all the answers. For now. Once uncertainty is identified, the next task is to minimize it. This is how we get closer to the truth.

At the institutional level, one counter to epistemic arrogance is asking questions. Even questions that may seem dumb. Especially questions that seem dumb. This needs to take place both within the institution, e.g. “why are we doing things like this?”, and external to the institution, e.g. “what is your basis for this decision?”. You know the annoying tendency where 4 year olds keep asking ‘why?’ to the most trivial of things? Emulate that. Eventually, such questioning will either reach a foundation, or it will be stonewalled with some variation of “we can’t share that information with you”. If a foundation is reached, examine it for epistemic arrogance versus humility. Are alternate options considered, or is it assumed that there is a perfect understanding? If you’re stonewalled, then you’ve either stumbled upon epistemic arrogance or you’ve just pissed off the person who was answering your questions. Probably both.

I believe it’s important to get this right. As society and technology become more complex and more interconnected, we rely more on the work and ideas of others. We need to have an honest understanding of what the limitations of both are, and where our models of each will break down. If a scientist publishes a paper on some new finding, is it true, or is it based on faulty assumptions that weren’t questioned due to arrogance? If a social activist says that if we just implement policy X, problem Y will vanish, is there an analysis based on data and reasoning with thoroughly thought-out consequences? Or are they burning down Chesterton’s fence based on ideology? We’ve seen several high-profile examples of epistemic arrogance over the years. It needs to be excised before the house of cards grows any bigger.

I think the weakest part of this post is the counter to institutional epistemic arrogance. It's also becoming increasingly important. If you can think of any other counters to institutional epistemic arrogance, please share them in this thread. Thank you!